In recent years, biochar has surged to the forefront of environmental science and sustainable agriculture discourse. But what precisely is biochar? It is a carbon-rich material produced through the pyrolysis of organic materials, such as agricultural residues, manure, and forestry waste. This intriguing substance not only sequesters carbon but also enhances soil properties, thereby intriguing scientists, farmers, and environmentalists alike. However, as we delve deeper into the latest studies surrounding biochar, one might ponder: Could this ancient practice of returning carbon to the soil actually be the key to addressing modern ecological challenges, or does it simply introduce new dilemmas?

To understand the potential of biochar, we must first examine its composition and production methods. Biochar is the product of thermal decomposition occurring in an oxygen-limited environment. The scientific community has made significant strides in optimizing the pyrolysis process, varying temperature, residence time, and feedstock types. As researchers investigate these variables, they uncover profound insights into the physical and chemical properties of biochar, such as its surface area, porosity, and nutrient retention capacity. How do these characteristics translate to agricultural productivity and ecosystem health?

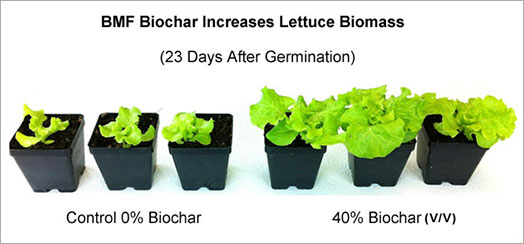

One of the most compelling advantages of biochar is its ability to improve soil fertility. Studies indicate that the application of biochar can significantly enhance nutrient availability, particularly in nutrient-poor soils. For instance, the presence of biochar increases cation exchange capacity (CEC)—the soil’s ability to hold positively charged ions—which can lead to better nutrient retention. Imagine transforming an arid landscape into a flourishing agricultural hub miraculously; it might be biochar that plays the role of an unsuspecting hero in this scenario.

Additionally, biochar is remarkably effective in retaining moisture, which paves the way for more resilient farming systems in the face of climate change. Some studies demonstrate that soils amended with biochar can retain up to 50% more water compared to those without. This characteristic is especially beneficial in drought-prone regions, where water scarcity poses a continual challenge. However, as we marvel at these benefits, a shadow lurks: what happens if biochar usage becomes widespread? Will it lead to an over-reliance on this singular solution, potentially sidelining other sustainable practices?

Another area of exploration is biochar’s role in carbon sequestration. The scientific community is enthusiastic about biochar’s potential to store carbon, effectively reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels when incorporated into soil. Some studies indicate that biochar can sequester carbon for hundreds to thousands of years. This promises not merely a short-term fix but rather a long-term solution in the fight against climate change. Yet, critical questions arise: how sustainable is biochar production? Are we inadvertently diverting essential crop residues or forest products that could have served other ecological functions?

Beyond its agricultural applications, biochar has also gained traction in addressing soil contamination, particularly heavy metal pollutants. Researchers are experimenting with biochar’s adsorption properties; specific types can capture heavy metals, thus mitigating their bioavailability and toxic effects on plants and the food chain. However, using biochar as a remediation technique brings forth ethical questions. Should we prioritize biochar applications in polluted areas, or can it serve equally well in pristine ecosystems? The stakes are high, and the implications are far-reaching.

In exploring the economic implications of biochar, the discussion becomes equally fascinating. As the environmental benefits become evident, the demand for biochar is on the rise. Agribusinesses and smallholder farmers alike are beginning to invest in biochar technology. Interestingly, certain studies illuminate the potential for biochar to not only reduce farm inputs but also generate additional income through carbon credits. The economic landscape could dramatically shift; however, the challenge lies in creating fair market structures that incentivize sustainable biochar production and application. Is the market prepared for this shift?

Moreover, the socio-political dimensions of biochar cannot be neglected. The implementation of biochar technology requires not just scientific acumen but also community buy-in and participation. Various studies highlight the need for education and outreach programs to inform farmers about the advantages and potential pitfalls of biochar application. Translation of scientific jargon into layman’s terms is paramount for widespread acceptance. Yet, there exists an inherent tension: can the benefits of biochar be equitably distributed to underserved communities without exacerbating existing disparities?

Research is still emerging, and the field of biochar is ripe with possibilities and unknowns. The synthesis of new data and studies provides a rich tapestry of information from which we can draw insights. Recent meta-analyses and reviews have attempted to consolidate findings regarding the impacts of biochar on different soil types, climatic conditions, and crop systems. Still, gaps in knowledge exist. Are there particular feedstocks that yield superior biochar quality? How do regional differences in soil microbiota affect biochar’s efficacy? The challenge remains to answer these queries, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of this multifaceted material.

Ultimately, biochar stands at the intersection of innovation and tradition, possessing the potential to reshape our ecological narrative. By interweaving ancient agricultural practices with cutting-edge research, biochar invites us on a journey through time, urging us to reconsider our relationship with the land. As humanity grapples with existential global challenges, biochar emerges not merely as a tool but as a symbol of hope. Will we embrace its potential to nourish the earth and its inhabitants or remain ensnared in the pitfalls of overreliance and commercialization? The answer lies not only in the research but also in our collective choices moving forward.