As the global climate crisis intensifies, the quest for solutions to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide has intensified as well. Among various strategies, composting has emerged as a surprisingly effective tool in the battle against climate change. But can compost truly sequester carbon? This question invites meticulous investigation into the myriad processes that intertwine organic decomposition with carbon storage.

The concept of carbon sequestration involves capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and storing it in a stable form to mitigate climate change. In this regard, composting serves as a formidable ally. When organic materials such as food scraps, yard waste, and other biodegradable substances break down, they do so through a complex interplay of microbial activity. During this decomposition process, certain carbon compounds are transformed into humus, a stable organic matter that sequesters carbon in the soil.

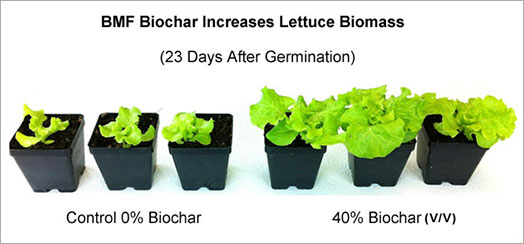

One might wonder how exactly compost contributes to this process. To unpack this, it is essential to delve into the biology of soil health. Healthy soil is brimming with microorganisms, which play a pivotal role in carbon dynamics. When compost is applied to the soil, it enhances microbial activity, promoting the development of a diverse soil ecosystem. This not only improves soil structure but also increases its capacity to store carbon. In fact, studies indicate that soils enriched with compost can hold up to 25% more carbon than those lacking such organic matter.

An equally vital consideration is the type of materials used in composting. Green materials—such as fresh grass clippings and kitchen scraps—are rich in nitrogen, while brown materials, like dried leaves and cardboard, provide carbon. The ideal composting process requires a delicate balance of greens and browns to maximize microbial activity and yield a nutrient-rich end product. Utilizing a variety of inputs not only fosters robust microbial communities but also enhances the biochemical stability of the resulting compost, further embedding carbon into the soil. The interplay of carbon to nitrogen ratios is fundamentally crucial and illustrates the sophistication of this natural phenomenon.

Furthermore, the longevity of the sequestered carbon in compost is noteworthy. Unlike conventional agricultural practices that often prioritize short-term yields, compost acts as a long-term investment in soil health. When organic matter decomposes, it eventually transforms into stable organic carbon. This form of carbon can persist in the soil for decades, if not centuries, thereby providing a sustainable method for reducing atmospheric CO2 levels. Some research suggests that compost application can lead to carbon retention rates of up to 10% per annum compared to unamended soils, showcasing a promising avenue for mitigating climate change.

Beyond its potential for carbon sequestration, composting has other ancillary benefits that enhance its appeal. For one, it reduces landfill waste—an important consideration, given that organic waste decomposing in landfills generates methane, a potent greenhouse gas. By diverting organic waste away from landfills and into composting systems, communities not only cut methane emissions but also create a valuable resource that enriches agricultural soil. This virtuous cycle embodies the principles of sustainability, as it incorporates waste reduction, soil health, and climate resilience into a cohesive framework.

However, it is important to remain cognizant of the limitations and context-dependent factors that influence the efficacy of composting as a carbon sequestration method. Climate, soil type, management practices, and garden design all play significant roles in determining the outcomes of compost application. For instance, in arid environments, the moisture retention properties of compost can mitigate the impact of drought, while in wetter climates, careful management is required to prevent nitrogen losses through leaching.

The early 21st century has witnessed a paradigm shift toward acknowledging the role of regenerative agricultural practices, including composting, as integral components of climate strategies. This shift is not merely theoretical; numerous communities are participating in initiatives aimed at enhancing composting practices. Urban compost initiatives thrive within metropolitan areas, where waste diversion is critical, while rural communities benefit from applying compost on large agricultural plots. Such collaborations exemplify how local actions can contribute to global climate solutions.

Intriguingly, more extensive research into the specific mechanisms of how compost enhances soil carbon storage remains a vital necessity. Understanding the intricacies of soil biology, chemistry, and physics in relation to compost will provide deeper insights into optimizing its carbon sequestration potential. Scientists are investigating microbial diversity, fungal networks, and their respective roles in carbon cycling, pushing the boundaries of our knowledge and revealing the underlying complexities of soil ecosystems.

In conclusion, the exploration of whether compost can effectively sequester carbon unveils both optimistic prospects and a wealth of scientific intrigue. As a multifaceted solution that aligns ecological health with climate change mitigation, composting reminds us of the interconnected nature of our ecosystem. This decentralized approach invites individuals and communities alike to participate actively in fostering a healthier planet. While further research is warranted, the science already suggests a paradigm that respects both nature’s resilience and humanity’s responsibility. Composting, it appears, harbors not just waste but the potential to revitalize our planet and sequester carbon in the process—a truly transformative notion for the age of climate consciousness.