In recent years, the term “biochar” has surged to the forefront of environmental discussions, piquing the curiosity of scientists, farmers, and eco-enthusiasts alike. At first glance, biochar may appear to be just another trendy concept in the realm of sustainability; however, its implications for carbon storage and climate change mitigation are profound. This article will delve into the science of biochar, its properties, production methods, applications, and the myriad benefits it poses for both agriculture and global carbon management.

Biochar is a form of charcoal produced by pyrolyzing organic materials—like wood chips, agricultural residues, and even manure—under low-oxygen conditions. The term itself is derived from “bio,” indicating its biological source, and “char,” a nod to its carbon-rich nature. The allure of biochar lies in its potential to sequester carbon for extended periods, providing a sustainable remedy for the increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels that exacerbate climate change.

One of the most compelling aspects of biochar is its unique structure. Unlike traditional charcoal, which is often used as a fuel, biochar possesses a porous architecture that enhances its efficacy in nutrient retention and soil modification. The surface area of biochar can reach up to several hundred square meters per gram, a critical factor when considering its role in supporting soil microorganisms and improving soil health. These micropores facilitate the absorption of water and nutrients, making them available to plant roots while concurrently reducing the leaching of essential nutrients into groundwater.

The carbon sequestration potential of biochar is particularly striking. When organic materials decompose naturally—via microbial processes—they release carbon back into the atmosphere as CO2. However, when these materials are subjected to pyrolysis to create biochar, most of the original carbon is retained in a stable form. This stability means that biochar can sequester carbon for hundreds or even thousands of years, a stark contrast to the fleeting nature of carbon cycling in traditional agricultural systems.

The production of biochar involves several methods, each varying in terms of temperature, feedstock type, and intended application. The two most prominent methods are fast pyrolysis and slow pyrolysis. Fast pyrolysis operates at higher temperatures (around 500 °C) and is optimized for producing liquid biofuels, while slow pyrolysis (around 350–500 °C) is geared towards maximizing char yield. Each method results in chemically distinct forms of biochar, which can be manipulated to achieve desired properties for specific agricultural needs.

A crucial aspect that often goes overlooked is the versatility of biochar types. With variations in feedstock and production methods, the resultant biochar can differ tremendously in chemical composition, ash content, and nutrient profile. For instance, biochar produced from hardwoods tends to have a higher carbon content than that derived from softwoods, making it more effective in carbon sequestration. This diversity allows farmers to select biochar suited not only to their soil type but also to the specific crops they wish to cultivate.

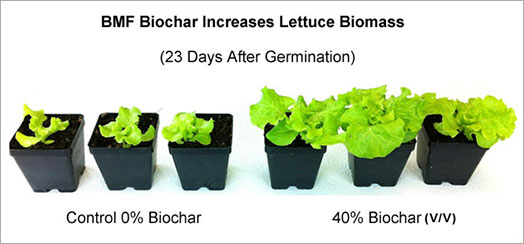

Biochar’s role in agriculture extends beyond simply improving soil quality. The addition of biochar can also enhance crop yields, promote healthier plant growth, and increase resilience to drought conditions. Research indicates that plants grown in biochar-amended soils demonstrate improved root development, greater nutrient uptake, and heightened stress resistance. In essence, biochar acts as a silent partner in the agricultural landscape, work harmoniously to enhance productivity while simultaneously acting as a carbon sponge.

In addition to its agricultural benefits, biochar holds immense potential in the context of environmental restoration. Land reclamation efforts can harness biochar to rehabilitate degraded soils, thus supporting the re-establishment of plant communities and improving biodiversity. Moreover, when utilized in constructed wetlands, biochar can filter pollutants and improve water quality by adsorbing excess nutrients and heavy metals, helping to mitigate eutrophication in freshwater ecosystems.

The intersection of biochar and climate policy is increasingly capturing attention. Policymakers are beginning to recognize the potential of biochar not only as a carbon storage solution but also as a tool for achieving emissions reduction targets. By integrating biochar into carbon credit schemes, farmers could be incentivized to produce and use biochar, thus creating a dual advantage—enhancing soil fertility while providing a new revenue stream through carbon credits.

Despite the burgeoning enthusiasm surrounding biochar, challenges persist that must be navigated to maximize its potential. Addressing issues surrounding scalability, economic viability, and public awareness is critical for promoting the widespread adoption of biochar technologies. Investments in research and development can foster innovations that streamline production processes and reduce costs, making biochar accessible to a broader spectrum of agricultural stakeholders.

In conclusion, biochar embodies a fascinating confluence of ancient wisdom and contemporary science. As a versatile tool for carbon storage, it offers a multi-faceted approach to tackling some of the planet’s most pressing issues, from soil degradation to climate change. Its enduring carbon sequestration capacity holds promise for future generations, positioning biochar not only as an agricultural enhancer but also as a critical component in our global strategy for carbon management and climate resilience. With continued research and renewed commitment from all sectors, biochar could truly become the unsung hero of the environmental movement.