As we navigate the complex terrain of climate change, innovative solutions are critically needed to mitigate the dire consequences of greenhouse gas emissions. One such solution that has gathered significant attention is biochar, a carbon-rich substance produced through the pyrolysis of organic materials. But as we explore the captivating potential of biochar, one must ponder: can this ancient practice truly revolutionize our approach to carbon sequestration, or will it just be another fleeting trend in environmental science?

Biochar has captured the imagination of scientists, farmers, and environmentalists alike. It offers a multifarious strategy for addressing the escalating carbon levels in our atmosphere. To understand the vast implications of biochar, it is essential to delve into its myriad benefits, the mechanisms behind its effectiveness, and the potential pitfalls that accompany its application.

What is biochar, exactly? At its core, biochar is a stable form of carbon created by heating organic materials—often derived from agricultural waste, forest residues, and even animal manure—at high temperatures in an oxygen-limited environment. This process, known as pyrolysis, not only produces biochar but also generates bio-oil and syngas, both of which can be utilized as renewable energy sources. The resultant biochar can then be incorporated into the soil, yielding a plethora of agronomic and environmental benefits.

One of the most compelling advantages of biochar lies within its ability to sequester carbon. When biochar is added to soil, it has the potential to store carbon for hundreds to thousands of years, thereby reducing the amount of carbon dioxide that can escape back into the atmosphere. This longevity is a result of biochar’s highly stable structure, which resists degradation and provides a consistent carbon sink. For those considering sustainable agriculture practices, biochar serves as a potent tool in their arsenal, offering farmers a dual advantage: enhancing soil health while simultaneously aiding in the fight against climate change.

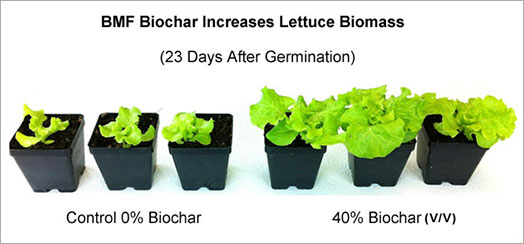

Beyond carbon sequestration, biochar boasts several remarkable properties that can significantly enhance soil fertility. Its porous structure creates a habitat for beneficial microorganisms, fostering an environment conducive to organic matter decomposition. This microbiological engagement results in improved nutrient availability, water retention, and overall soil structure. Farmers who have integrated biochar into their cultivation practices report enhanced crop yields, reduced reliance on chemical fertilizers, and an uptick in soil resilience against drought conditions. A veritable win-win, isn’t it?

However, while the potential of biochar appears almost utopian, it is crucial to explore the challenges and limitations associated with its widespread implementation. The journey to a biochar-dominant agricultural landscape is not without its obstacles. One significant concern lies in the scalability of biochar production. Although pyrolysis technology is advancing, harnessing biochar at a global scale demands substantial investment, technological innovation, and a well-established infrastructure. Extrapolating the needs of diverse agricultural systems can lead to variability in biochar quality, which may dilute its anticipated benefits. Wouldn’t it be ironic if a solution to climate change simply became a costly endeavor?

A further complication arises concerning the sourcing of raw materials for biochar production. Many practitioners advocate for utilizing biomass that would otherwise be wasted, aligning biochar production with principles of sustainability. However, the competition for biomass can engender conflicts with other industries, such as those relying on agricultural residues for energy or animal feed. Balancing these competing demands will require robust governance and strategic planning to ensure that biochar production serves as a benefit rather than a detriment to local ecosystems.

Moreover, biochar’s interactions with soil can be as complex as they are beneficial. For instance, certain types of biochar may lead to changes in soil pH, potentially affecting nutrient dynamics and microbial communities. Additionally, the leaching of toxic compounds from some biochar products can be a source of concern. Therefore, diligence in selecting and testing biochar types is paramount to ensure its positive impact on soil health.

It is also essential to consider the socioeconomic implications of biochar adoption. While its environmental benefits are promising, there is a risk that it could create a divide between wealthy and marginalized farming communities. Farmers with the means to invest in biochar may thrive, while those lacking resources could face challenges in adapting to these new practices. Comprehensive education, equitable access to technology, and fair policy development must be integral to any biochar initiative aimed at fostering sustainability.

In summary, biochar emerges as a multifaceted tool in our quest to address climate change, possessing the remarkable ability to sequester carbon while enriching soils. It holds promise for farmers seeking more sustainable practices, leading to enhanced crop yields and environmental stewardship. Yet, this seemingly panacea also presents a series of challenges that must be addressed. From production scalability and resource competition to ecological repercussions and socioeconomic disparities, the path toward biochar implementation is fraught with complexity.

As we stand at this crossroads, will we embrace the transformative potential of biochar, or will we allow the associated pitfalls to deter progress? The answer may very well shape the future of our agricultural landscapes and our planet’s climate.