Biochar, an intriguing derivative of biomass, is generated through a process called slow pyrolysis. This method, defined by its methodical heating of organic material in the absence of oxygen, reveals a world of possibilities for carbon sequestration and sustainable agriculture. With an increasing urgency to confront climate change, researchers and agricultural scientists are looking beyond conventional practices. They are veering toward innovative techniques such as biochar, which promises a transformative shift in perspectives on soil health, waste management, and carbon capture.

At its essence, biochar is a stable form of carbon that possesses remarkable properties. Being the end product of slow pyrolysis, it retains the structural integrity of its organic origins while simultaneously enhancing soil fertility. As anyone involved in sustainable land management knows, the key to productive farmland hinges on soil quality. Biochar serves as a potent amendment to improve aeration, water retention, and nutrient availability in the soil. Its porous structure enables it to hold onto essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which are vital for plant growth.

Addressing the process of slow pyrolysis first, it is important to understand the intricacies that set it apart from other thermal processes. Unlike fast pyrolysis, which produces liquid bio-oil, slow pyrolysis is characterized by lower temperatures, longer residence times, and minimal reactive gases. This method, operating at temperatures typically ranging from 350°C to 700°C, results in the production of solid biochar, gas, and a small amount of liquid. The slow pyrolysis process ensures the retention of carbon, creating a stable, highly porous material that can sequester carbon in the soil for centuries, thus combatting atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

An essential aspect of biochar’s allure lies in its ability to address the twin crises of soil degradation and climate change. In many agricultural scenarios, soil degradation manifests through erosion, loss of nutrients, and increased salinity, which hampers productivity. Integrating biochar into conventional farming practices offers a twofold solution. First, it enhances the soil’s structure and promotes beneficial microbial activity, both paramount for a resilient ecosystem. Second, by sequestering carbon, biochar participates in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. This attribute has placed biochar squarely on the radar of climate action initiatives globally.

One of the most compelling arguments for adopting biochar is its versatility and applicability across diverse environments and soil types. Whether for urban gardens, commercial agriculture, or reforestation efforts, biochar can be tailored to meet specific ecological needs. In arid regions, for example, the introduction of biochar can enhance soil moisture retention, substantially improving crop yields in water-scarce environments. Conversely, in nutrient-poor soils, biochar can help retain essential minerals, rendering poor soils fertile over time.

Importantly, the benefits of biochar extend beyond just soil improvement. The process of creating biochar also addresses waste management challenges. Agricultural residues, forestry waste, and organic waste from urban areas can be transformed into biochar, which not only mitigates landfill use but also reduces methane emissions from decomposing organic matter. This circular economy approach provides a dual advantage—solving waste issues while simultaneously enriching agricultural practices.

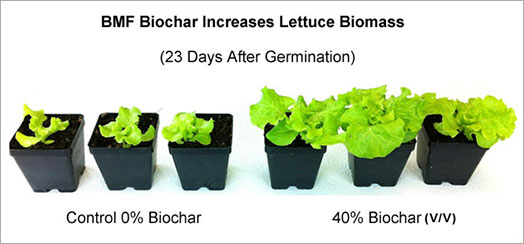

Moreover, the application of biochar exhibits an intriguing linkage with mitigation strategies in food production. With global food demand projected to soar, there is an urgent need to ensure high-yield and sustainable farming practices. Biochar has shown promising results extending crop productivity, which is critical for food security. Studies indicate that crops grown in biochar-amended soils have outperformed those grown traditionally, showcasing increased resilience to drought and pest pressures. This interaction between biochar and plant systems offers a tantalizing glimpse into an agricultural revolution.

However, as with any innovative approach, the successful implementation of biochar is not without its challenges. The efficacy of biochar can depend on its feedstock type, production conditions, and application rates. Furthermore, the need for extensive research into the long-term effects of biochar on ecosystem dynamics remains crucial. As scientists dissect the complexities of its impact on soil biology and carbon cycles, ongoing studies continue to refine application methodologies, making biochar a more reliable tool for sustainable practices.

The discourse around biochar is multifaceted, encapsulating environmental, agricultural, and economic paradigms that collectively reframe our understanding of sustainable practices. As curiosity burgeons in both scholarly circles and public discourse, biochar serves as a nexus of innovation—perched at the intersection of climate action and soil stewardship. By embracing this fusion of science and agronomy, we can contemplate a sustainable future marked by personal agency toward reimagining land use.

In summary, biochar, produced through the slow pyrolysis of organic material, emerges as a multifactorial solution that transcends traditional agricultural boundaries. It enriches soil health, combats climate change by sequestering carbon, and addresses waste management challenges—situating itself at the forefront of environmental remediation and sustainable agriculture. As we stride further into the 21st century, an amplified understanding of biochar’s potential is essential, as it may well serve as the lodestar guiding us toward a more sustainable future.