What is a substance so simple yet so profoundly impactful that it has the potential to transform our approach to climate change and soil health alike? Enter biochar: a carbon-rich, charcoal-like material produced through the pyrolysis of organic material. This process not only captures carbon in a stable form, which might otherwise contribute to atmospheric CO2, but also provides immense benefits for agricultural practices and soil management. However, as promising as biochar may be, it begs the question: Can this ancient method stand up to modern agricultural demands and environmental challenges?

To understand the significance of biochar, it is vital to delve into its origins and the mechanism behind its creation. Biochar is generated by heating organic matter—such as agricultural residues, wood chips, or even manure—in a low-oxygen environment. This thermochemical conversion process eliminates volatile substances, resulting in a stable form of carbon that can endure in soil for hundreds or even thousands of years. As we grapple with a climate crisis driven by greenhouse gas emissions, this stability becomes an argument for biochar’s role as a formidable ally in carbon sequestration efforts.

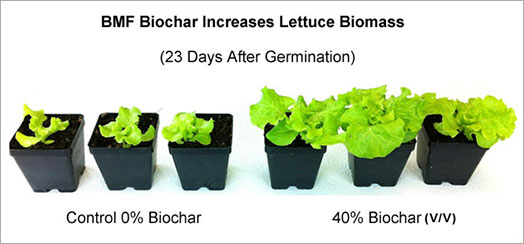

However, the real allure of biochar extends beyond its carbon capture capabilities. The unique porous structure of biochar enhances its adsorption properties, which in turn facilitates improved soil fertility. It acts as a sponge for nutrients and water, allowing for better moisture retention and limiting nutrient leaching. Moreover, its high surface area provides countless microhabitats, fostering beneficial microbial communities essential for soil health and plant growth.

This remarkable ability to improve soil attributes highlights biochar’s dual functionality. By bolstering soil fertility, it not only enhances crop yields but also mitigates some challenges posed by climate change. For instance, during periods of drought, biochar-treated soils can maintain better moisture levels; conversely, in flood-prone areas, biochar can improve drainage. Yet, the challenge remains: Is there a one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to biochar applications across diverse geographies and agricultural systems?

Harvesting the benefits of biochar isn’t a universal endeavor. Different types of biochar exist, each with distinct properties depending on the feedstock used and the specific pyrolysis conditions. This variation plays a significant role in determining its effect on soil health and crop performance. As such, farmers and land managers must become biochar connoisseurs, carefully selecting the right type to suit their local environment and specific agricultural goals. The key lies in understanding local soil characteristics and climate conditions to tailor biochar application effectively.

Given its increasing popularity, numerous studies and experiments have sprung up worldwide. These range from small-scale organic farms incorporating biochar for soil improvement to large-scale carbon offset projects focusing on reforestation efforts in degraded lands. Countries like Australia, Brazil, and Ethiopia are at the forefront of these initiatives, witnessing transformational results from their adoption of biochar in regenerative agriculture practices. The enthusiasm around this eco-friendly solution, however, necessitates a prudent approach to ensure that the process does not devolve into a checklist of best practices devoid of community engagement. How can we strike a balance?

The community-centric aspect is vital for the sustainable adoption of biochar initiatives. Stakeholders across the agricultural value chain—farmers, agricultural scientists, policy-makers, and non-governmental organizations—must collaborate to create awareness and best practices concerning biochar application. Engaging local communities brings attention to socio-economic benefits as well, such as improved food security and rural development opportunities—often lost in the conversation about carbon credits and environmental impacts alone.

Additionally, while the utility of biochar is becoming increasingly evident, skepticism remains about its scalability. Can biochar production keep pace with the growing demand for sustainable agricultural practices? And more importantly, will the initial investment required for biochar technology deter farmers from its adoption? Addressing these concerns necessitates innovative approaches to production and education, leveraging both technology and local knowledge bases.

As the world grapples with the realities of climate change, biochar stands as a beacon of hope. It merges ancient practices with modern science, offering solutions that are as versatile as they are compelling. The challenge is not just about understanding biochar but rather fostering a culture of experimentation and adaptation within various agricultural sectors. By ensuring an inclusive dialogue that emphasizes local context and community involvement, we can illuminate the path towards utilizing biochar as a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture. Ultimately, the innovative promise of biochar lies in its ability to integrate seamlessly into existing systems, bolstering productivity while nurturing the planet. Will we rise to this challenge, harnessing the potential of biochar to cultivate both our soil and our future? Only time—and our commitment—will tell.